Building a reliable embedded system involves far more than getting code to compile. It’s a process of learning where hardware limits, timing guarantees, and data representation quietly shape everything above them.

Week 2 of the Plan focused on making those constraints explicit.

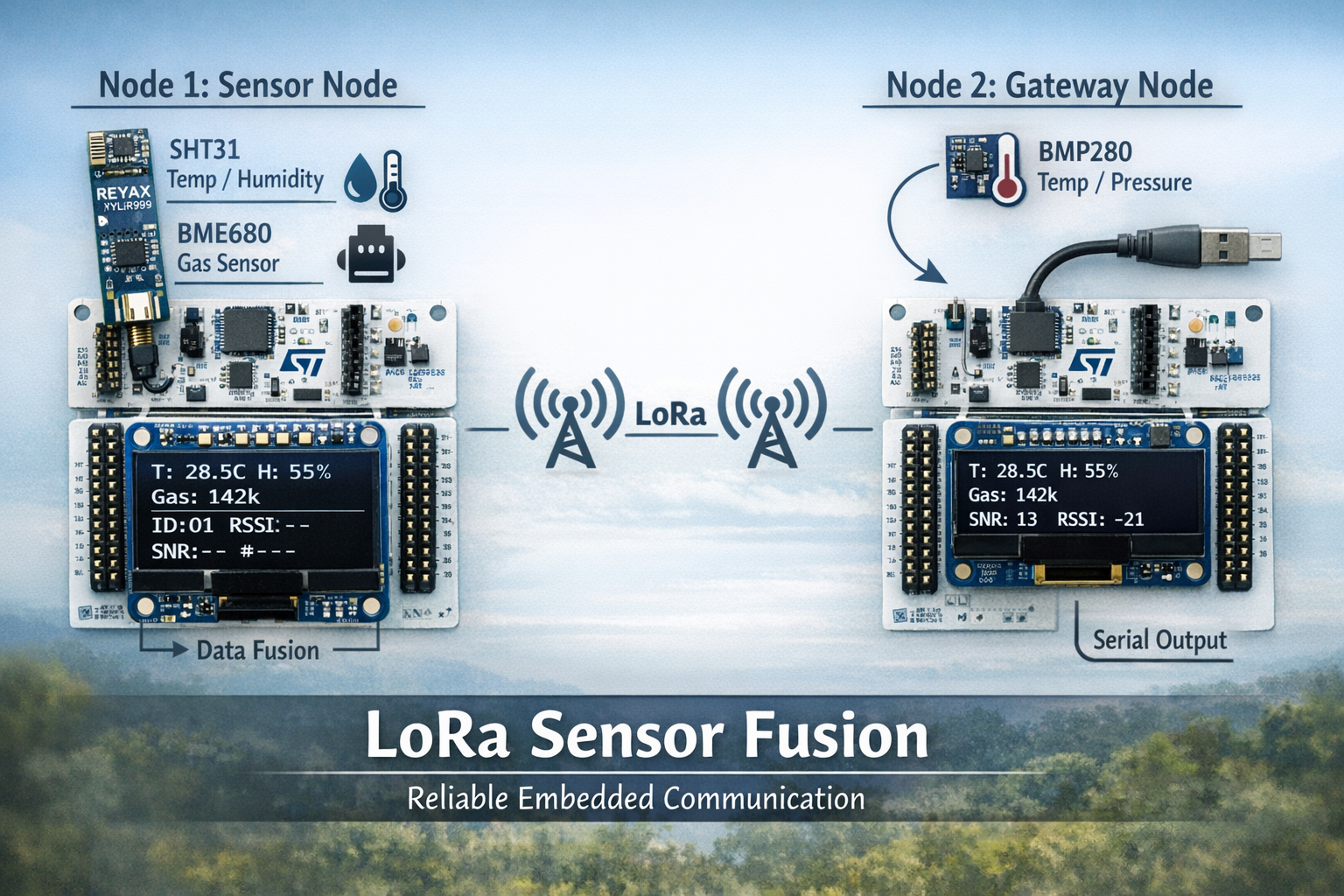

The result is a dual-node LoRa sensor fusion system built on the STM32F446RE using Rust and RTIC 1.1 — not as a showcase, but as a foundation.

Table of Contents

The Objective

The goal for this week was deliberately narrow:

- Build a two-node LoRa system

- Fuse data from multiple sensors on the transmitting node

- Display and verify the data locally

- Receive, parse, and observe it on a second node

No cloud.

No dashboards.

No retries or binary framing yet.

Just a system that behaves predictably end-to-end.

This constraint was intentional. Before moving to binary protocols, CRC validation, or retry logic, the foundation must be solid. Week 2 was about making that foundation explicit.

System Overview

The system consists of two cooperating nodes:

Node 1 — The Sensor Node

Hardware:

- STM32F446RE (Cortex-M4F @ 84 MHz)

- SHT31-D for temperature and humidity

- BME680 for gas resistance (VOC indication)

- SSD1306 OLED 128×64 display

- REYAX RYLR998 LoRa module (UART @ 115,200 baud)

Function:

- Samples environmental sensors at 1 Hz

- Displays measurements locally on OLED

- Transmits fused telemetry via LoRa

Node 2 — The Gateway

Hardware:

- STM32F446RE (Cortex-M4F @ 84 MHz)

- BMP280 for local temperature/pressure reference

- SSD1306 OLED 128×64 display

- REYAX RYLR998 LoRa module (UART @ 115,200 baud)

Function:

- Receives LoRa packets

- Displays decoded sensor values

- Shows signal quality metrics (RSSI/SNR)

- Provides sanity checks with local BMP280

Communication Protocol: The nodes use the LoRa module’s AT command interface — intentionally simple and inspectable at this stage. Example transmission:

AT+SEND=0,20,T:28.5H:55.2G:142\r\n

Where:

T:28.5= Temperature in °C (from SHT31)H:55.2= Humidity in % RH (from SHT31)G:142= Gas resistance in kΩ (from BME680)

Five Critical Lessons

Week 2 taught five lessons about constraints, each one exposing a hidden assumption or design flaw. Together, they transformed an unreliable prototype into a predictable system.

Lesson 1: The 51-Byte Myth (and a Self-Inflicted Limit)

The Symptom

Early tests revealed a puzzling problem: LoRa packets were being truncated. Only 28–30 bytes of each message arrived intact at the receiver.

A 40-byte payload would arrive as:

T:28.5H:55.2G:142k

But a 50-byte payload would be cut off mid-transmission:

T:28.52H:55.24G:142kOhm Pres

The Initial Hypothesis

At first glance, this looked like a LoRa limitation. In LoRaWAN contexts, a 51-byte payload cap is often cited due to regional regulations and duty cycle restrictions.

But the RYLR998 is not LoRaWAN. It’s a simple point-to-point LoRa transceiver. The datasheet clearly states it supports payloads up to 240 bytes.

The Real Culprit

The limit turned out to be self-imposed.

Both the transmit and receive paths were using heapless::String buffers sized far too conservatively:

// Original (too small)

let mut tx_buffer: String<32> = String::new();

let mut rx_buffer: String<32> = String::new();

At 32 bytes, these buffers couldn’t hold full AT commands with sensor data. The RYLR998’s AT command format includes overhead:

AT+SEND=0,<len>,<payload>\r\n

A payload of 20 bytes requires ~30 bytes total once you include the command wrapper. The 32-byte buffer was barely sufficient, and any additional data would overflow.

The Fix

The solution was simple but instructive:

// Corrected (255 bytes to match LoRa module capability)

let mut tx_buffer: String<255> = String::new();

let mut rx_buffer: String<255> = String::new();

Size operations based on actual payload length, not assumptions:

write!(tx_buffer, "AT+SEND=0,{},{}\r\n", payload.len(), payload)?;

The Lesson

Embedded constraints don’t just come from hardware — they also come from our own defensive choices.

This was a reminder to:

- Read datasheets carefully (240 bytes, not 51)

- Question “common knowledge” (LoRaWAN limits don’t apply to point-to-point LoRa)

- Size buffers based on actual requirements, not conservative guesses

Lesson 2: RTIC Timing (When Helpful Code Becomes Harmful)

The New Symptom

After fixing the buffer sizes, a second issue emerged: scrambled data.

Packets arrived, but characters were:

- Missing

- Reordered

- Corrupted

Example received payload:

T:28H:55.2G4k // Expected: T:28.5H:55.2G:142k

The root cause wasn’t LoRa at all — it was timing.

Understanding UART at 115,200 Baud

At 115,200 baud with 8N1 configuration (8 data bits, no parity, 1 stop bit), each byte requires 10 bit times:

Byte time = 10 bits ÷ 115,200 bits/sec ≈ 86.8 µs

A new byte arrives every ~87 microseconds.

If the UART interrupt handler takes longer than 87 µs to execute, the next byte will arrive before the previous one is fully processed. The hardware FIFO will overflow, and bytes will be lost.

The Harmful Code

During debugging, I had added diagnostic logic to the UART interrupt handler:

#[task(binds = UART4, shared = [lora_uart, display], priority = 2)]

fn uart4_handler(ctx: uart4_handler::Context) {

let uart = ctx.shared.lora_uart;

let display = ctx.shared.display;

(uart, display).lock(|uart, display| {

if let Ok(byte) = uart.read() {

// ❌ BAD: Expensive operations in ISR

defmt::debug!("RX: {:02x}", byte); // RTT logging (slow!)

rx_buffer.push(byte).ok();

if byte == b'\n' {

// ❌ WORSE: I2C transaction in ISR!

update_display(display, &rx_buffer);

}

}

});

}

Problems:

- RTT logging (

defmt::debug!) is synchronous and slow (~hundreds of µs) - Display updates involve I2C transactions (~milliseconds)

- Resource locking adds overhead

At 115,200 baud, these operations easily exceed the 87 µs budget. The result: missed bytes.

The RTIC Lesson

RTIC makes this lesson painfully clear:

Interrupt handlers must stay fast and boring.

The UART handler’s job was reduced to the absolute minimum:

#[task(binds = UART4, shared = [lora_uart], priority = 2)]

fn uart4_handler(ctx: uart4_handler::Context) {

let uart = ctx.shared.lora_uart;

uart.lock(|uart| {

if let Ok(byte) = uart.read() {

// ✅ GOOD: Fast operations only

rx_buffer.push(byte).ok();

// Detect message boundary

if byte == b'\n' {

// ✅ GOOD: Spawn lower-priority task

process_message::spawn().ok();

}

}

});

}

#[task(shared = [display], priority = 1)]

fn process_message(ctx: process_message::Context) {

// ✅ This runs at lower priority, won't block UART

let display = ctx.shared.display;

display.lock(|display| {

// Parse rx_buffer

// Update display

// Log results

});

}

Everything else — parsing, display updates, I2C traffic — was moved to slower, scheduled tasks at lower priority.

The Result

Once that separation was enforced:

- The data stream became clean and repeatable

- No more missed bytes

- No more scrambled packets

The rule: Interrupt handlers do one thing: service the hardware. Everything else happens in background tasks.

Lesson 3: Sensor Fusion by Selection, Not Averaging

The Design Question

With two sensors capable of measuring temperature and humidity (SHT31 and BME680), the obvious question is: How do we combine their readings?

Common approaches:

- Average the two readings

- Weight them based on stated accuracy

- Use Kalman filtering or sensor fusion algorithms

The Honest Answer

I chose none of the above.

Instead, the system uses sensor selection:

| Measurement | Sensor | Accuracy | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | SHT31 | ±0.3°C | Dedicated high-precision sensor |

| Humidity | SHT31 | ±2% RH | Superior to BME680 (±3% RH), no burn-in required |

| Gas Resistance | BME680 | N/A | Unique capability (VOC detection) |

| Pressure | BME680* | ±1 hPa | Available but not transmitted (Week 2) |

The BME680 contributes only gas resistance data. Other channels from the BME680 are available, but intentionally unused.

Why This Approach?

Clarity beats cleverness at this stage of the learning plan.

Reasons:

- Clear provenance: Every value has a documented source

- No hidden assumptions: No averaging hides sensor limitations

- Explainable behavior: Easier to debug when something goes wrong

- Honest about limitations: We’re not pretending to have better data than we do

Could I implement Kalman filtering? Yes. Would it improve the readings? Probably marginally. Would it obscure the underlying constraints? Absolutely.

The Lesson

Sensor fusion isn’t always about blending data. Sometimes it’s about choosing the right tool for each job.

This keeps the system honest and maintainable. At Week 2, that matters more than squeezing out an extra 0.1°C of accuracy.

Lesson 4: Units, Displays, and Small Lies That Matter

The Temperature Confusion

Early in Week 2, the OLED displayed alarming readings:

T:2852C H:5520%

A temperature of 2,852°C would vaporize the sensor. A humidity of 5,520% violates physics.

The problem wasn’t the sensor — it was data representation.

Understanding Sensor Units

The SHT31-D reports measurements in fixed-point format:

| Measurement | Unit | Example Raw | Actual Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | centidegrees Celsius | 2852 | 28.52°C |

| Humidity | basis points (0.01%) | 5520 | 55.20% RH |

A value like 2852 isn’t an error — it’s just 28.52°C represented as an integer.

Why this format?

- Avoids floating-point arithmetic on resource-constrained MCUs

- Preserves precision without IEEE-754 overhead

- Common in embedded sensor protocols

The Fix

Proper unit conversion before display:

// Temperature: centidegrees → degrees Celsius

let temp_c = raw_temp as f32 / 100.0;

// Humidity: basis points → percentage

let humidity_pct = raw_humidity as f32 / 100.0;

// Display

write!(line1, "T:{:.1}C H:{:.0}%", temp_c, humidity_pct)?;

Result:

T:28.5C H:55%

Another Small Lie: OLED Y-Coordinate Clipping

During display optimization, I noticed that text starting at y = 0 had clipped ascenders:

// ❌ Clips ascenders (top of 'h', 'l', etc.)

Text::new("Hello", Point::new(0, 0), style)

// ✅ Proper baseline offset

Text::new("Hello", Point::new(0, 8), style)

The y coordinate in embedded-graphics represents the baseline, not the top-left corner. Starting at y = 0 places ascenders above the display area.

The Lesson

Small misunderstandings propagate quickly in embedded systems if left unchecked.

Neither of these is a dramatic failure. But in a more complex system:

- A temperature off by 100× could trigger false alarms

- Clipped text could hide critical warnings

This is why the OLED exists in this project: not as a UI, but as an always-on sanity check.

Lesson 5: Shared Hardware Forces Honest Design

The I2C Bus Sharing Problem

All sensors and the OLED share a single I2C bus:

- SHT31-D (address:

0x44) - BME680 (address:

0x77) - SSD1306 OLED (address:

0x3C) - BMP280 (Node 2 only, address:

0x76)

In C or C++, you might just access the bus whenever you need it. In Rust, this is not something you can “just make work.”

Rust’s Ownership Rules

Rust enforces exclusive mutable access at compile time. The I2C peripheral can have only one owner.

You must explicitly decide:

- Who owns the bus?

- When can it be accessed?

- Under what guarantees?

Trying to share without proper synchronization results in compile errors:

// ❌ Doesn't compile

let sht31 = SHT31::new(i2c); // Takes ownership

let bme680 = BME680::new(i2c); // Error: i2c already moved

The Solution: shared-bus Crate

The shared-bus crate provides mutex-based bus sharing:

use shared_bus::BusManagerSimple;

// Create a bus manager

let bus_manager = BusManagerSimple::new(i2c);

// Create proxies for each device

let sht31 = SHT31::new(bus_manager.acquire_i2c());

let bme680 = BME680::new(bus_manager.acquire_i2c());

let display = Ssd1306::new(bus_manager.acquire_i2c(), ...);

Each acquire_i2c() returns a mutex-protected proxy. When a device accesses the bus, it:

- Acquires the mutex

- Performs the I2C transaction

- Releases the mutex

This ensures safe, serialized access without runtime ambiguity or data races.

The RTIC Integration

In RTIC, shared resources are protected by priority-based preemption:

#[shared]

struct Shared {

display: Ssd1306<...>,

sht31: SHT31<...>,

bme680: BME680<...>,

}

#[task(shared = [display, sht31], priority = 1)]

fn update_sensors(ctx: update_sensors::Context) {

let sht31 = ctx.shared.sht31;

let display = ctx.shared.display;

(sht31, display).lock(|sht31, display| {

// Critical section: I2C transactions are atomic

let reading = sht31.measure()?;

display.show(reading)?;

});

}

RTIC guarantees that higher-priority tasks can preempt, but shared resources are protected by software-based critical sections.

The Lesson

Rust doesn’t let you defer architectural decisions.

It makes you confront them early, when the system is still small enough to reason about.

This is a recurring theme in the Plan: constraints that seem restrictive in Week 2 become guardrails in Week 10 when the system has 10× more components.

Results at the End of Week 2

By the end of the week, the system worked predictably and reliably:

Communication Metrics

| Metric | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LoRa Range | ~5 meters (indoor) | Limited by test environment |

| RSSI | -20 to -22 dBm | Excellent signal strength |

| SNR | ~13 dB | Clean reception, no interference |

| Packet Loss | 0% | After buffer/timing fixes |

| Update Rate | 1 Hz | Stable, deterministic |

Data Quality

| Sensor | Measurement | Range Observed | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHT31 | Temperature | 22–30°C | Indoor ambient |

| SHT31 | Humidity | 40–65% RH | Varied with weather |

| BME680 | Gas Resistance | 50–200 kΩ | VOC baseline established |

System Behavior

Most importantly, the system’s behavior was explainable.

- Data had clear provenance (SHT31 for temp/humidity, BME680 for gas)

- Timing was deterministic (1 Hz sampling, <87 µs ISR)

- Buffers were sized correctly (255 bytes, not 32)

- Display showed real-time sanity checks

- LoRa transmission worked end-to-end

Nothing surprised me.

When I changed the sensor sampling rate, the display updated at the new rate.

When I moved the nodes farther apart, RSSI decreased predictably.

When I added debug logging to a low-priority task, it didn’t break anything.

This is what “reliable” looks like at Week 2: not perfect, but understandable.

Why This Matters in the Plan

Week 2 is not about performance or optimization.

It’s about reaching a point where:

- ✅ Data has a clear origin (sensor selection, not blending)

- ✅ Timing is intentional (ISRs stay fast, tasks run at appropriate priorities)

- ✅ Constraints are understood (buffer sizes, UART byte timing, I2C bus sharing)

- ✅ Failures are diagnosable (OLED sanity checks, explainable behavior)

Only then does it make sense to move on to binary serialization, framing, CRCs, and retries.

The Philosophical Point

Reliability is not added later.

It is built up, one unglamorous layer at a time.

Consider the alternative approach:

- Build a complex system with binary protocols, encryption, and cloud integration

- Debug mysterious failures for weeks

- Add more logging, more retries, more complexity

- Still can’t explain why packets occasionally drop

That’s backwards.

The right sequence:

- Week 2: Make simple things work predictably

- Week 3: Add binary serialization while preserving predictability

- Week 4: Add CRC validation while preserving predictability

- Week 5: Add retransmission while preserving predictability

Each layer builds on a solid, understood foundation.

What Week 2 Enables

By the end of this week, I can:

- Explain every byte in the LoRa transmission

- Predict timing behavior of UART and I2C operations

- Diagnose failures by looking at the OLED display

- Modify the system without introducing mysterious bugs

That foundation is what makes Week 3’s binary protocol work possible.

Week 2 laid that layer.

Next Steps: Week 3 Preview

With a reliable ASCII-based system in place, Week 3 will focus on:

Binary Serialization

Replace human-readable AT commands:

T:28.5H:55.2G:142\r\n

With compact binary frames:

[Header][Length][Temp][Humidity][Gas][CRC16]

Benefits:

- Reduced payload size (20 bytes → 12 bytes)

- Deterministic parsing (no string operations)

- CRC validation for data integrity -準備 for multi-packet messages

CRC Data Integrity

Implement CRC-16-CCITT for error detection:

- Detect bit flips from RF interference

- Validate packet integrity before processing

- Foundation for ACK/NACK protocol

Protocol Framing

Add packet structure:

struct TelemetryPacket {

header: u8, // 0xAA

packet_id: u16, // Incremental counter

temp: i16, // Centidegrees

humidity: u16, // Basis points

gas: u32, // Ohms

crc: u16, // CRC-16-CCITT

}

Lessons to Carry Forward

Week 3 will build on Week 2’s constraints:

- Timing: Binary parsing must stay fast (still <87 µs per byte)

- Buffers: Size for binary frames, not ASCII

- Sanity checks: OLED displays binary fields in human-readable format

- Explainability: CRC failures logged and displayed

The goal remains the same: make complexity understandable.

Conclusion

Week 2 taught that constraints aren’t limitations — they’re guardrails.

- Buffer sizes force you to understand payload limits

- UART timing forces you to write fast interrupt handlers

- Rust’s ownership rules force you to design I2C access carefully

- Data representation forces you to document units

Each constraint revealed an assumption. Each lesson made the system more honest.

This is the path to reliability: not through cleverness, but through understanding and respecting constraints.

Next week, those constraints won’t go away. They’ll just become more explicit as we add binary protocols.

And that’s exactly how it should be.

Resources

Code Repository

Related Posts

Technical References

Author: Antony (Tony) Mapfumo

Part of: 4-Month Embedded Rust Learning Roadmap

Week: 2 of 16

Tags: #embedded-rust #rtic #lora #stm32 #sensor-fusion #iot #learning-in-public