1. Introduction

I come from a networking background. For years, my world revolved around packets, routing tables, latency, and uptime. Over time, it became clear that the boundary between IT and OT (Operational Technology) was becoming less rigid as industrial systems moved onto standard IP networks. Networks were no longer just carrying business traffic — they were increasingly responsible for transporting sensor data, telemetry, and control signals from the physical world. That realization pushed me toward Industrial IoT (IIoT) and, inevitably, embedded systems.

Industrial environments demand something very different from hobby electronics or web backends. They demand predictability, reliability, and correctness under constraints. A temperature sensor that occasionally crashes is annoying at home; in an industrial setting, it can mean downtime, damaged equipment, or safety risks. I wanted a foundation that takes correctness seriously, without sacrificing performance or control.

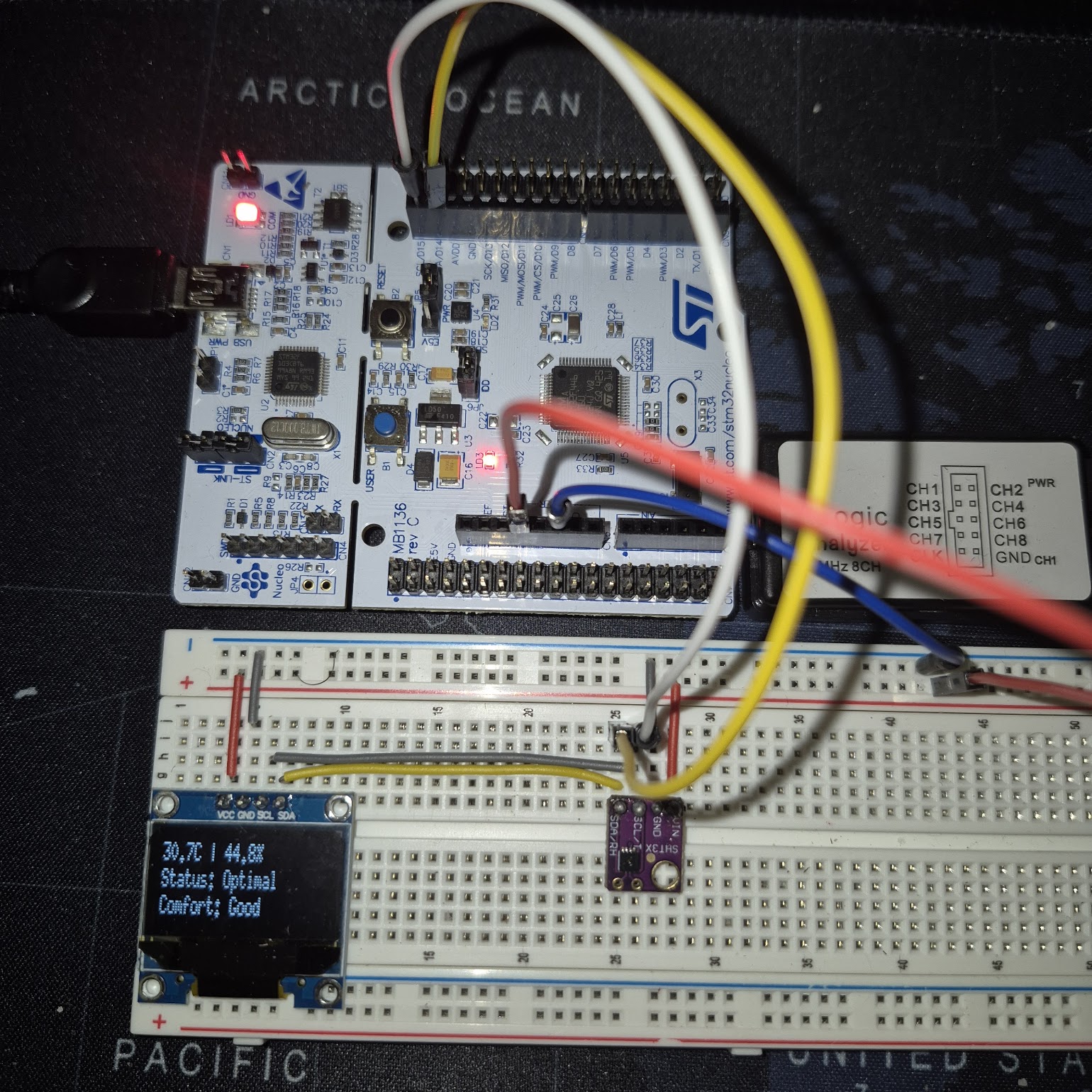

This project — an IIoT temperature and humidity sensor node built with Embedded Rust on an STM32F446RE — is part of that transition. It is intentionally simple in scope, but deliberate in design. No operating system. No heap. No dynamic allocation. Just a microcontroller, a high-accuracy sensor, and a small display, tied together with explicit, auditable code.

Three months ago, I had never used a soldering iron. Today, I have a fully operational sensor node. This journey from a beginner to a functioning IIoT system illustrates that determination and methodical learning can rapidly turn a novice into someone capable of building professional-grade embedded systems.

In this post, I’ll walk through the motivation, hardware choices, software architecture, and the very real challenges encountered along the way. If you’re a network engineer curious about embedded systems, or an embedded developer evaluating Rust for production, this project is meant to be a practical, grounded example.

2. Why Embedded Rust?

Memory Safety Without Garbage Collection

Rust’s most compelling feature for embedded work is memory safety without a garbage collector. In industrial systems, unpredictability is the enemy. A GC pause — even a short one — can be unacceptable. Rust’s ownership model enforces rules at compile time that prevent entire classes of bugs: use-after-free, double-free, data races, and many buffer overflows.

In C or C++, avoiding these issues relies heavily on discipline, code review, and testing. In Rust, the compiler enforces those constraints relentlessly. You don’t get to “be careful”; you must be correct.

Zero-Cost Abstractions

Rust allows you to write expressive, high-level code that compiles down to the same machine instructions you would write by hand. Traits, generics, and abstractions disappear at compile time. There is no runtime penalty for doing things the right way.

For embedded systems — where cycles, memory, and power matter — this is critical. You get clarity without overhead.

Growing Embedded Ecosystem

The embedded Rust ecosystem has matured significantly. HAL crates abstract vendor-specific peripherals. Sensor and display drivers build on embedded-hal traits. The Embedded Working Group actively coordinates improvements across tooling, documentation, and libraries.

It’s not perfect, but it’s real — and improving fast.

Industry Adoption

Rust is no longer experimental. It’s used by companies like Cloudflare and AWS, and it’s making inroads into automotive and safety-critical domains. In IIoT, where devices are deployed for years and often unattended, safety and reliability are not optional. Rust aligns naturally with those requirements.

3. Hardware Selection: STM32F446RE

Why STM32 for IIoT?

STM32 microcontrollers are an industry staple. They are widely available, well-documented, and proven in industrial deployments. The STM32F446RE in particular offers a strong balance of performance and resources:

- Cortex-M4F running at up to 180 MHz

- Hardware floating-point unit

- 128 KB RAM

- 512 KB Flash

- Rich peripheral set: I2C, SPI, UART, CAN, timers

This is more than enough for a sensor node while leaving headroom for communication stacks and future features.

NUCLEO Development Board

The NUCLEO-F446RE board simplifies development:

- Built-in ST-LINK debugger (no external probe needed)

- Arduino-compatible headers for rapid prototyping

- Widely available and affordable

It removes friction and lets you focus on the system, not the setup.

Sensor Selection

For environmental sensing, I chose the Sensirion SHT31-D:

- ±0.2°C temperature accuracy

- ±2% relative humidity accuracy

- I2C interface

- Fast startup and low power consumption

Temperature and humidity are foundational signals in many IIoT domains, from smart buildings to manufacturing and cold-chain logistics.

4. System Architecture

High-Level Overview

SHT31-D ─┐

├── I2C ── STM32F446RE ── OLED Display

SSD1306 ─┘ |

└── (Future) Wireless / MQTT

This node reads environmental data from the SHT31-D and displays it locally on a small OLED. The design intentionally keeps everything on a shared I2C bus.

Shared I2C Bus Design

Multiple devices on a single I2C bus introduce a subtle challenge in Rust: ownership. Only one owner can access the bus at a time, but both the sensor and the display need it.

The solution is the shared-bus crate, which provides safe, mutex-like sharing without runtime overhead. This prevents bus conflicts and makes access explicit.

Software Architecture

no_stdenvironment- No heap allocation

- HAL-based peripheral access

- Polling-based design for simplicity

Polling is a deliberate choice here. For a sensor updating every two seconds, interrupts add complexity without meaningful benefit.

Data Flow

- Trigger measurement on the SHT31-D

- Read temperature and humidity

- Format values into fixed-capacity buffers

- Update OLED display

- Repeat

Future extensions include forwarding this data over LoRa or MQTT.

5. Development Journey: Challenges & Solutions

Challenge 1: Embedded-HAL Version Mismatch

The embedded Rust ecosystem is evolving, and not all crates move in lockstep. In this project:

stm32f4xx-halusesembedded-hal1.0shared-busdepends onembedded-hal0.2

The solution was to depend on both versions simultaneously, renaming one at import time. It’s not elegant, but it’s effective.

Lesson: Version pinning is non-negotiable in embedded Rust.

Challenge 2: The Alternating Error Bug

The sensor initially worked — but only every second read. The root cause was an incorrect I2C transaction sequence. The SHT31-D expects a write command followed by a delay and then a read. Combining these incorrectly led to intermittent failures.

Separating the transactions and respecting the datasheet timing resolved the issue.

Lesson: Datasheets are not optional reading.

Challenge 3: String Formatting Without a Heap

In no_std, there is no String. Display output still requires formatting human-readable text.

The solution was heapless::String with fixed capacity. It forces you to think explicitly about buffer sizes and stack usage.

Lesson: Stack vs heap trade-offs become explicit — and that’s a good thing.

Challenge 4: SSD1306 Driver Versions

Newer versions of the SSD1306 driver introduced trait conflicts. Pinning to a known-good version restored stability.

Lesson: Stability often beats novelty in production-oriented systems.

6. Code Walkthrough

Key components include:

- Sensor initialization and measurement triggering

- Explicit I2C read/write sequences

- Fixed-capacity formatting buffers

- Graceful handling of non-critical errors

Non-critical failures (like a missed display update) are tolerated, while critical errors fail loudly.

Full source code is available here:

https://github.com/mapfumo/sht31-d-nucleo

7. Where This Design Fits in the Real World

This project is intentionally modest in scope. It is not a control system, and it is not designed for hard real-time actuation. That constraint is a feature, not a limitation. Many industrial problems are about monitoring, evidence, and trend detection rather than immediate control. In those contexts, simplicity and reliability matter more than complexity or performance.

Below are environments where this exact design — or a lightly adapted version of it — fits naturally.

Agriculture and Controlled Environments

Greenhouses, crop storage facilities, and drying operations depend heavily on stable temperature and humidity ranges. Failures are often gradual rather than catastrophic: reduced yield, spoilage, or quality degradation over time.

A small, deterministic sensor node deployed at multiple locations provides localized visibility without complex infrastructure. Polling-based designs are sufficient, power consumption can be optimized, and long service life matters more than high update rates. This node fits that profile well.

Cold Chain and Logistics

In food and pharmaceutical logistics, the problem is often not just control but proof. Regulations and quality assurance require evidence that environmental conditions stayed within acceptable bounds throughout transport and storage.

A reliable temperature and humidity node provides auditable data with minimal software complexity. When combined with a gateway that periodically forwards measurements, this design supports traceability without embedding unnecessary logic at the edge.

Manufacturing and Process Monitoring

Many manufacturing processes are sensitive to environmental drift rather than sudden failure. Temperature or humidity trends can affect material properties, tolerances, or equipment behavior long before alarms are triggered.

This project deliberately avoids an RTOS and interrupt-heavy design. For non-control monitoring tasks, predictability, auditability, and ease of reasoning often matter more than microsecond-level responsiveness. The architecture reflects that priority.

These examples are not exhaustive, but they demonstrate a consistent theme: this design targets environments where reliability, simplicity, and clear data flow are more valuable than complexity or raw performance.

8. Scaling to a Multi-Node Network

The current system is a single node with a local display. Natural next steps include:

- LoRa for long-range, low-power communication

- A gateway node bridging LoRa to MQTT

- Centralized dashboards (InfluxDB + Grafana)

This evolves the design from a device into a system.

9. Performance & Reliability

- Flash usage: ~28 KB

- RAM usage: ~6 KB

- Update rate: 2 seconds

- Power consumption: ~55 mA active

Rust’s compile-time guarantees, combined with explicit error handling, provide a strong reliability baseline.

10. Lessons Learned

- Version pinning matters

- Logic analyzers are invaluable (Wireshark for hardware)

- Datasheets save time in the long run

- Public documentation multiplies the value of your work

For network engineers moving into embedded systems: your protocol knowledge, debugging mindset, and security awareness transfer directly.

11. Getting Started

git clone https://github.com/mapfumo/sht31-d-nucleo.git

cd sht31-d-nucleo

cargo build --release

cargo run --release

Hardware cost is modest, and the toolchain is entirely open.

12. What’s Next?

- MQTT gateway integration

- Time-series storage and dashboards

- Industrial protocols (Modbus, OPC-UA)

- Wireless sensor networks

This project is a foundation, not a finish line. For future versions of this node, frameworks like Embassy Rust may be considered. Embassy provides async/await concurrency on bare-metal MCUs, which could simplify handling multiple sensors, non-blocking I2C/SPI operations, and low-power scheduling. For the current single-sensor design, a simple polling loop remains sufficient and predictable.

13. Conclusion

This project demonstrates that Embedded Rust is not theoretical — it’s practical, efficient, and well-suited to IIoT systems. With explicit design, strong tooling, and careful constraints, it’s possible to build systems that are both safe and performant.

If you’re curious, clone the repo, experiment, and extend it. IIoT needs reliable systems — and Rust is a strong candidate for building them.